-

For a regular cardinal κκ, a formula of the modal μμ-calculus is

κκ-continuous in a variable x if, on every model, its interpretation as a

unary function of x is monotone and preserves unions of κκ-directed sets.

We define the fragment Cℵ1(x)Cℵ1(x) of the modal μμ-calculus and prove

that all the formulas in this fragment are ℵ1ℵ1-continuous. For each

formula ϕ(x)ϕ(x) of the modal μμ-calculus, we construct a formula ψ(x)∈Cℵ1(x)ψ(x)∈Cℵ1(x) such that ϕ(x)ϕ(x) is κκ-continuous, for some

κκ, if and only if ϕ(x)ϕ(x) is equivalent to ψ(x)ψ(x). Consequently, we

prove that (i) the problem whether a formula is κκ-continuous for some

κκ is decidable, (ii) up to equivalence, there are only two fragments

determined by continuity at some regular cardinal: the fragment

Cℵ0(x)Cℵ0(x) studied by Fontaine and the fragment Cℵ1(x)Cℵ1(x). We

apply our considerations to the problem of characterizing closure ordinals of

formulas of the modal μμ-calculus. An ordinal αα is the closure

ordinal of a formula ϕ(x)ϕ(x) if its interpretation on every model converges

to its least fixed-point in at most αα steps and if there is a model

where the convergence occurs exactly in αα steps. We prove that

ω1ω1, the least uncountable ordinal, is such a closure ordinal. Moreover

we prove that closure ordinals are closed under ordinal sum. Thus, any formal

expression built from 0, 1, ωω, ω1ω1 by using the binary operator

symbol + gives rise to a closure ordinal.

-

We show that dyon and magnetic monopole can be constructed in the

gauge-independent way for the SU(2)SU(2) Yang--Mills theory even in the absence of

the scalar field. This result is derived from the recent proposal for obtaining

non-trivial topological configurations responsible for quark confinement in the

Yang-Mills theory based on the Confinement-Higgs complementary relationship

between the pure Yang-Mills theory and the gauge-scalar model with an adjoint

scalar field of the fixed length. We discuss how such configurations have the

implications for quark confinement.

-

The band structure of an Si inverse diamond structure whose lattice point

shape was vacant regular octahedrons, was calculated using plane wave expansion

method. A complete photonic band gap was theoretically confirmed at around 0.4

THz. It is said that three-dimensional photonic crystals have no polarization

anisotropy in photonic band gap (stop gap, stop band) of high symmetry points

in normal incidence. However, it was experimentally confirmed that the

polarization orientation of a reflected wave was different from that of an

incident wave, [I(X,Y)(X,Y)], where (X,Y)(X,Y) is the coordinate system fixed in the

photonic crystal. It was studied on a plane (001) at around X point's photonic

band gap (0.36 −− 0.44 THz) for incident wave direction [001] by rotating a

sample in the plane (001), relatively. The polarization orientation of the

reflected wave was parallel to that of the incident wave when that of the

incident wave was I(1, 1) or I(1, −−1). In contrast, the former was

perpendicular to the latter when that of the incident wave was I(1, 0) or I(0,

−−1) at around 0.38 THz. As far as the photonic crystal in this work is

concerned, method of resolution and synthesis of the incident polarization

vector is not able to apply to the analyses of rotation of the measured

reflected spectra in appearance.

-

The presence of certain clinical dermoscopic features within a skin lesion

may indicate melanoma, and automatically detecting these features may lead to

more quantitative and reproducible diagnoses. We reformulate the task of

classifying clinical dermoscopic features within superpixels as a segmentation

problem, and propose a fully convolutional neural network to detect clinical

dermoscopic features from dermoscopy skin lesion images. Our neural network

architecture uses interpolated feature maps from several intermediate network

layers, and addresses imbalanced labels by minimizing a negative multi-label

Dice-F11 score, where the score is computed across the mini-batch for each

label. Our approach ranked first place in the 2017 ISIC-ISBI Part 2:

Dermoscopic Feature Classification Task challenge over both the provided

validation and test datasets, achieving a 0.895% area under the receiver

operator characteristic curve score. We show how simple baseline models can

outrank state-of-the-art approaches when using the official metrics of the

challenge, and propose to use a fuzzy Jaccard Index that ignores the empty set

(i.e., masks devoid of positive pixels) when ranking models. Our results

suggest that (i) the classification of clinical dermoscopic features can be

effectively approached as a segmentation problem, and (ii) the current metrics

used to rank models may not well capture the efficacy of the model. We plan to

make our trained model and code publicly available.

-

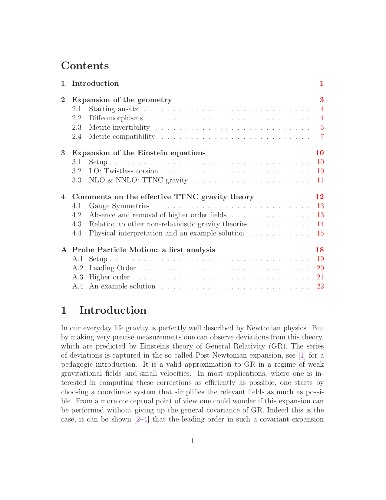

We revisit the manifestly covariant large cc expansion of General

Relativity, cc being the speed of light. Assuming the relativistic connection

has no pole in c−2c−2, this expansion is known to reproduce Newton-Cartan

gravity and a covariant version of Post-Newtonian corrections to it. We show

that relaxing this assumption leads to the inclusion of twistless torsion in

the effective non-relativistic theory. We argue that the resulting TTNC theory

is an effective description of a non-relativistic regime of General Relativity

that extends Newtonian physics by including strong gravitational time dilation.

-

The rapid growth of IoT driven by recent advancements in consumer

electronics, 5G communication technologies, and cloud-computing enabled

big-data analytics, has recently attracted tremendous attention from both the

industry and academia. One of the major open challenges for IoT is the limited

network lifetime due to massive IoT devices being powered by batteries with

finite capacities. The low-power and low-complexity backscatter communications

(BackCom), which simply relies on passive reflection and modulation of an

incident radio-frequency (RF) wave, has emerged to be a promising technology

for tackling this challenge. However, the contemporary BackCom has several

major limitations, such as short transmission range, low data rate, and

uni-directional information transmission. The article aims at introducing the

recent advances in the active area of BackCom. Specifically, we provide a

systematic introduction of the next generation BackCom covering basic

principles, systems, techniques besides IoT applications. Lastly, we describe

the IoT application scenarios with the next generation BackCom.

-

We prove that square-tiled surfaces having fixed combinatorics of horizontal

cylinder decomposition and tiled with smaller and smaller squares become

asymptotically equidistributed in any ambient linear GL(R)-invariant

suborbifold defined over Q in the moduli space of Abelian

differentials. Moreover, we prove that the combinatorics of the horizontal and

of the vertical decompositions are asymptotically uncorrelated. As a

consequence, we prove the existence of an asymptotic distribution for the

combinatorics of a "random" interval exchange transformation with integer

lengths.

We compute explicitly the absolute contribution of square-tiled surfaces

having a single horizontal cylinder to the Masur-Veech volume of any ambient

stratum of Abelian differentials. The resulting count is particularly simple

and efficient in the large genus asymptotics. We conjecture that the

corresponding relative contribution is asymptotically of the order 1/d, where

d is the dimension of the stratum, and prove that this conjecture is

equivalent to the long-standing conjecture on the large genus asymptotics of

the Masur-Veech volumes. We prove, in particular, that the recent results of

Chen, M\"oller and Zagier imply that the conjecture holds for the principal

stratum of Abelian differentials as the genus tends to infinity.

Our result on random interval exchanges with integer lengths allows to make

empirical computation of the probability to get a 1-cylinder pillowcase cover

taking a "random" one in a given stratum. We use this technique to derive the

approximate values of the Masur-Veech volumes of strata of quadratic

differentials of all small dimensions.

-

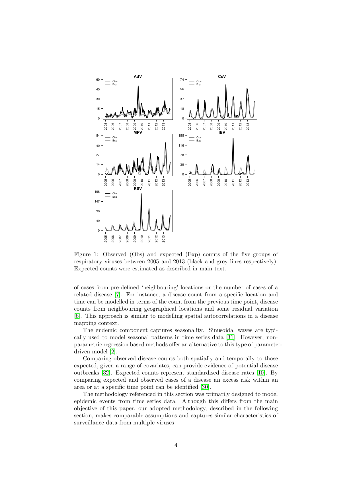

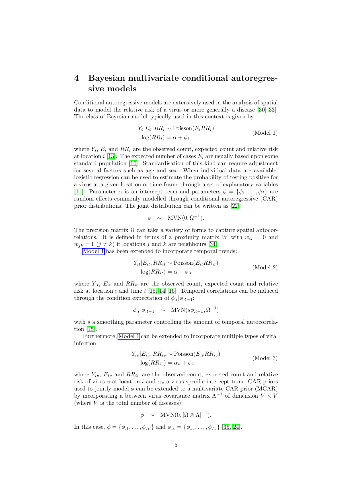

It is well recognised that animal and plant pathogens form complex ecological

communities of interacting organisms within their hosts. Although community

ecology approaches have been applied to determine pathogen interactions at the

within-host scale, methodologies enabling robust inference of the

epidemiological impact of pathogen interactions are lacking. Here we developed

a novel statistical framework to identify statistical covariances from the

infection time-series of multiple pathogens simultaneously. Our framework

extends Bayesian multivariate disease mapping models to analyse multivariate

time series data by accounting for within- and between-year dependencies in

infection risk and incorporating a between-pathogen covariance matrix which we

estimate. Importantly, our approach accounts for possible confounding drivers

of temporal patterns in pathogen infection frequencies, enabling robust

inference of pathogen-pathogen interactions. We illustrate the validity of our

statistical framework using simulated data and applied it to diagnostic data

available for five respiratory viruses co-circulating in a major urban

population between 2005 and 2013: adenovirus, human coronavirus, human

metapneumovirus, influenza B virus and respiratory syncytial virus. We found

positive and negative covariances indicative of epidemiological interactions

among specific virus pairs. This statistical framework enables a community

ecology perspective to be applied to infectious disease epidemiology with

important utility for public health planning and preparedness.

-

To allow for Division By Zero, we develop a new algebraic structure

containing addition and multiplication called an S-Extension of a Field. This

unique structure extends a Field so that the equation 0⋅s=x has exactly

one solution for every non-zero Field element x. Furthermore, a different

solution is obtained for each choice of x, making this solution unique to

that particular equation. However, the equation 0⋅s=0 has two or more

solutions, with no preference towards any one particular solution. This allows

us to use the usual definition of division as the solution to the equation

0⋅s=x to evaluate x divided by 0. And if x≠0, every x0 is a unique element that is also unique to that particular x while

00 remains indeterminate. This creates a Division By Zero which

significantly differs from other attempts at Division By Zero.

-

The complex method of interpolation, going back to Calder\'on and Coifman et

al., on the one hand, and the Alexander-Wermer-Slodkowski theorem on polynomial

hulls with convex fibers, on the other hand, are generalized to a method of

interpolation of real (finite-dimensional) Banach spaces and of convex

functions. The underlying duality in this method is given by the Legendre

transform. Our results can also be interpreted as new properties of solutions

of the homogeneous complex Monge-Amp\`ere equation.

-

Q-systems and T-systems are systems of integrable difference equations

that have recently attracted much attention, and have wide applications in

representation theory and statistical mechanics. We show that certain

τ-functions, given as matrix elements of the action of the loop group of

GL2 on two-component fermionic Fock space, give solutions of a

Q-system. An obvious generalization using the loop group of GL3

acting on three-component fermionic Fock space leads to a new system of 4

difference equations.

-

This paper studies fractional integral operator for vector fields in weighted

L1. Using the estimates on fractional integral operator and Stein-Weiss

inequalities, we can give a new proof for a class of Caffarelli-Kohn-Nirenberg

inequalities and establish new \divg-\curl inequalities for vector fields.

-

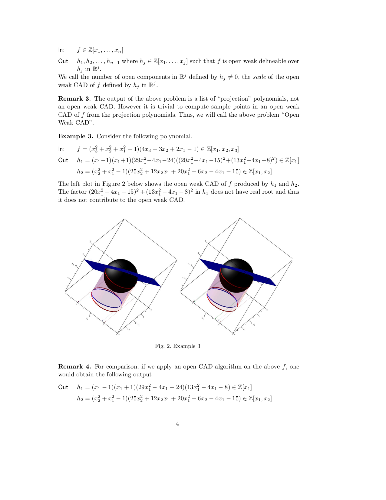

The concept of open weak CAD is introduced. Every open CAD is an open weak

CAD. On the contrary, an open weak CAD is not necessarily an open CAD. An

algorithm for computing projection polynomials of open weak CADs is proposed.

The key idea is to compute the intersection of projection factor sets produced

by different projection orders. The resulting open weak CAD often has smaller

number of sample points than open CADs. The algorithm can be used for computing

sample points for all open connected components of f≠0 for a given

polynomial f. It can also be used for many other applications, such as

testing semi-definiteness of polynomials and copositive problems. In fact, we

solved several difficult semi-definiteness problems efficiently by using the

algorithm. Furthermore, applying the algorithm to copositive problems, we find

an explicit expression of the polynomials producing open weak CADs under some

conditions, which significantly improves the efficiency of solving copositive

problems.

-

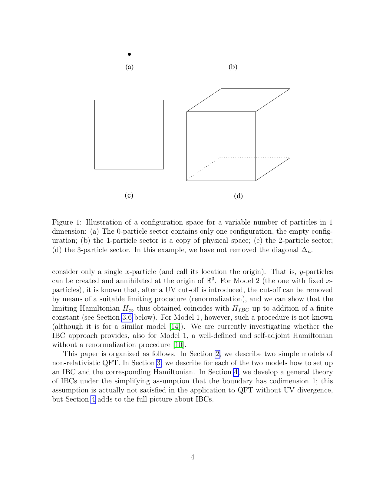

We propose a way of defining Hamiltonians for quantum field theories without

any renormalization procedure. The resulting Hamiltonians, called IBC

Hamiltonians, are mathematically well-defined (and in particular, ultraviolet

finite) without an ultraviolet cut-off such as smearing out the particles over

a nonzero radius; rather, the particles are assigned radius zero. These

Hamiltonians agree with those obtained through renormalization whenever both

are known to exist. We describe explicit examples of IBC Hamiltonians. Their

definition, which is best expressed in the particle-position representation of

the wave function, involves a kind of boundary condition on the wave function,

which we call an interior-boundary condition (IBC). The relevant configuration

space is one of a variable number of particles, and the relevant boundary

consists of the configurations with two or more particles at the same location.

The IBC relates the value (or derivative) of the wave function at a boundary

point to the value of the wave function at an interior point (here, in a sector

of configuration space corresponding to a lesser number of particles).

-

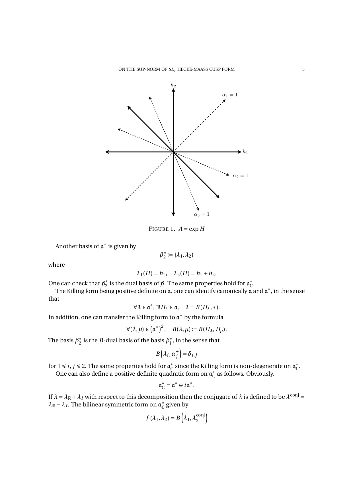

This work contains a proof of a non-trivial explicit quantitative bound in

the eigenvalue aspect for the sup-norm of a SL(3,Z) Hecke-Maass cusp form

restricted to a compact set.

-

A C*-dynamical system is said to have the ideal separation property if every

ideal in the corresponding crossed product arises from an invariant ideal in

the C*-algebra. In this paper we characterize this property for unital

C*-dynamical systems over discrete groups. To every C*-dynamical system we

associate a "twisted" partial C*-dynamical system that encodes much of the

structure of the action. This system can often be "untwisted," for example when

the algebra is commutative, or when the algebra is prime and a certain specific

subgroup has vanishing Mackey obstruction. In this case, we obtain relatively

simple necessary and sufficient conditions for the ideal separation property. A

key idea is a notion of noncommutative boundary for a C*-dynamical system that

generalizes Furstenberg's notion of topological boundary for a group.

-

The Tur\'an function ex(n,F) denotes the maximal number of edges in an

F-free graph on n vertices. We consider the function hF(n,q), the

minimal number of copies of F in a graph on n vertices with ex(n,F)+q

edges. The value of hF(n,q) has been extensively studied when F is

bipartite or colour-critical. In this paper we investigate the simplest

remaining graph F, namely, two triangles sharing a vertex, and establish the

asymptotic value of hF(n,q) for q=o(n2).

-

We investigate the universal cover of a topological group that is not

necessarily connected. Its existence as a topological group is governed by a

Taylor cocycle, an obstruction in 3-cohomology. Alternatively, it always exists

as a topological 2-group. The splitness of this 2-group is also governed by an

obstruction in 3-cohomology, a Sinh cocycle. We give explicit formulas for both

obstructions and show that they are inverse of each other.

-

Semidefinite programs (SDPs) -- some of the most useful and versatile

optimization problems of the last few decades -- are often pathological: the

optimal values of the primal and dual problems may differ and may not be

attained. Such SDPs are both theoretically interesting and often impossible to

solve; yet, the pathological SDPs in the literature look strikingly similar.

Based on our recent work \cite{Pataki:17} we characterize pathological

semidefinite systems by certain {\em excluded matrices}, which are easy to spot

in all published examples. Our main tool is a normal (canonical) form of

semidefinite systems, which makes their pathological behavior easy to verify.

The normal form is constructed in a surprisingly simple fashion, using mostly

elementary row operations inherited from Gaussian elimination. The proofs are

elementary and can be followed by a reader at the advanced undergraduate level.

As a byproduct, we show how to transform any linear map acting on symmetric

matrices into a normal form, which allows us to quickly check whether the image

of the semidefinite cone under the map is closed. We can thus introduce readers

to a fundamental issue in convex analysis: the linear image of a closed convex

set may not be closed, and often simple conditions are available to verify the

closedness, or lack of it.

-

Tensor hierarchies are algebraic objects that emerge in gauging procedures in

supergravity models, and that present a very deep and intricate relationship

with Leibniz (or Loday) algebras. In this paper, we show that one can

canonically associate a tensor hierarchy to any Loday algebra. By formalizing

the construction that is performed in supergravity, we build this tensor

hierarchy explicitly. We show that this tensor hierarchy can be canonically

equipped with a differential graded Lie algebra structure that coincides with

the one that is found in supergravity theories.

-

In the genomic era, the identification of gene signatures associated with

disease is of significant interest. Such signatures are often used to predict

clinical outcomes in new patients and aid clinical decision-making. However,

recent studies have shown that gene signatures are often not replicable. This

occurrence has practical implications regarding the generalizability and

clinical applicability of such signatures. To improve replicability, we

introduce a novel approach to select gene signatures from multiple datasets

whose effects are consistently non-zero and account for between-study

heterogeneity. We build our model upon some rank-based quantities, facilitating

integration over different genomic datasets. A high dimensional penalized

Generalized Linear Mixed Model (pGLMM) is used to select gene signatures and

address data heterogeneity. We compare our method to some commonly used

strategies that select gene signatures ignoring between-study heterogeneity. We

provide asymptotic results justifying the performance of our method and

demonstrate its advantage in the presence of heterogeneity through thorough

simulation studies. Lastly, we motivate our method through a case study

subtyping pancreatic cancer patients from four gene expression studies.

-

The neural network is a powerful computing framework that has been exploited

by biological evolution and by humans for solving diverse problems. Although

the computational capabilities of neural networks are determined by their

structure, the current understanding of the relationships between a neural

network's architecture and function is still primitive. Here we reveal that

neural network's modular architecture plays a vital role in determining the

neural dynamics and memory performance of the network of threshold neurons. In

particular, we demonstrate that there exists an optimal modularity for memory

performance, where a balance between local cohesion and global connectivity is

established, allowing optimally modular networks to remember longer. Our

results suggest that insights from dynamical analysis of neural networks and

information spreading processes can be leveraged to better design neural

networks and may shed light on the brain's modular organization.

-

We propose a general framework for nonasymptotic covariance matrix estimation

making use of concentration inequality-based confidence sets. We specify this

framework for the estimation of large sparse covariance matrices through

incorporation of past thresholding estimators with key emphasis on support

recovery. This technique goes beyond past results for thresholding estimators

by allowing for a wide range of distributional assumptions beyond merely

sub-Gaussian tails. This methodology can furthermore be adapted to a wide range

of other estimators and settings. The usage of nonasymptotic dimension-free

confidence sets yields good theoretical performance. Through extensive

simulations, it is demonstrated to have superior performance when compared with

other such methods. In the context of support recovery, we are able to specify

a false positive rate and optimize to maximize the true recoveries.

-

Recently representation theory has been used to provide atomic decompositions

for a large collection of classical Banach spaces. In this paper we extend the

techniques to also include projective representations. As our main application

we obtain atomic decompositions of Bergman spaces on the unit ball through the

holomorphic discrete series for the group of isometries of the ball.

-

This article proves that an irreducible subfactor planar algebra with a

distributive biprojection lattice admits a minimal 2-box projection generating

the identity biprojection. It is a generalization (conjectured in 2013) of a

theorem of Oystein Ore on distributive intervals of finite groups (1938), and a

corollary of a natural subfactor extension of a conjecture of Kenneth S. Brown

in algebraic combinatorics (2000). We deduce a link between combinatorics and

representations in finite group theory.